The Great Trees of London from Time Out

Dear Readers, as the whole purpose of this blog is (ostensibly) to look at wildlife in London, it will come as no surprise that I have amassed a collection of books on urban flora and fauna. Let’s start with The Great Trees of London, which is a small but beautifully-formed guide to the an award which was born out of the terrible storm of 1987. In 1997, the public were asked to nominate London’s ‘Great Trees’. To qualify, they had to be publicly accessible, and have either historical significance or imposing physical stature. If it was in some way a landmark this was also taken into consideration. 41 trees made the cut, followed by another 20 in 2008. One of the many things that I plan to do in retirement is to visit all of them, and I have already featured one or two: the Totteridge Yew was an early subject, as was the Marylebone elm. This is a snappily -written book, and it has the added advantage of fitting into a largish handbag for when one goes exploring (whenever that becomes a possibility). I’m sure that there are champion trees all over the world, and they are always well worth getting to know.

Next, another little guide that has found me several sites for birdwatching: David Darrell Lambert’s Birdwatching London. I have had this book for ages, but only just noticed what fun the front cover was. That is surely the photo of a lifetime.

I am indebted to this book for not only indicating where things like heronries are, but also for alerting me to the smaller nature reserves such as the Greenwich Peninsula Ecology Park and East India Dock Basin, which I would probably otherwise not have known existed. I can see my retirement becoming even busier with all these sites to visit.

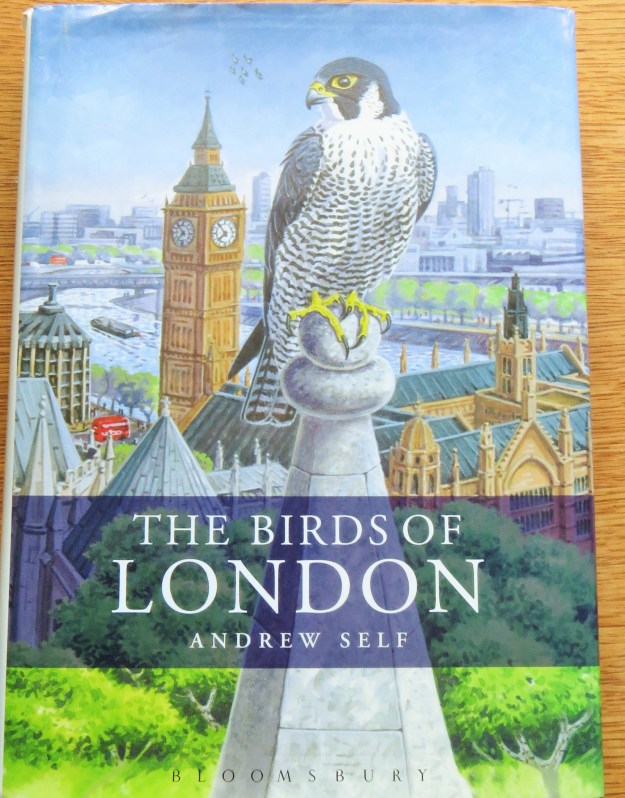

One of my ambitions is to see some little owls (i.e. the species, not some diminutive individuals) and according to my next book, ‘The Birds of London’ by Andrew Self, there are at least 30 pairs in Richmond Park (and several in Regent’s Park and Kensington Gardens). Although this book is definitely for information rather than fun, it can be a fascinating read: it follows each species’ decline and fall over the past few hundred years, and gives an indication of where they can be found today.

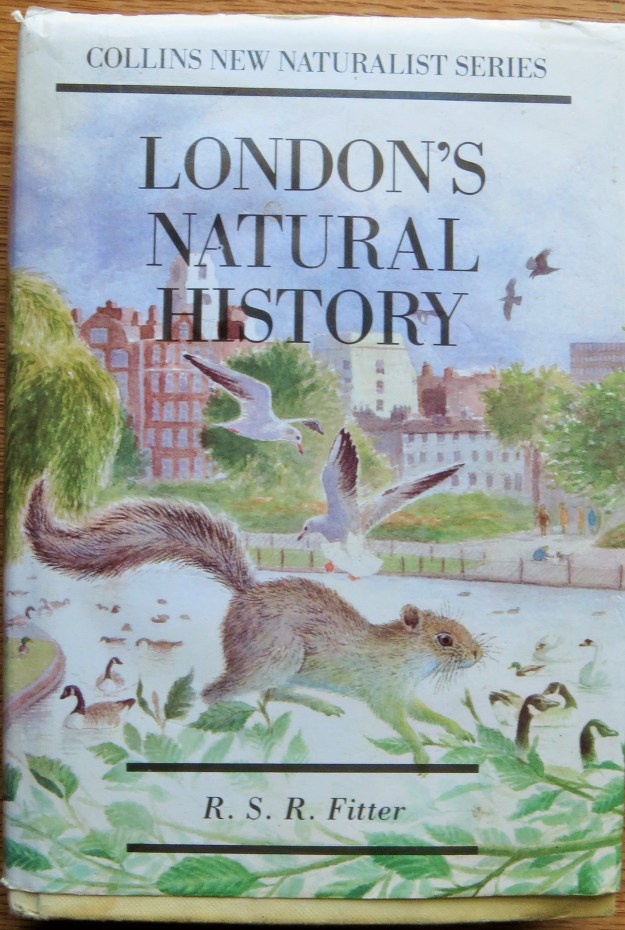

But I have left my favourite till last. ‘London’s Natural History’ by Richard Fitter was first published in 1945, and every page has a fascinating titbit. I learned, for example, that Epping Forest was the last redoubt of the red squirrel in London at the time the book was written, but all was not as it seemed: in 1910 a local landowner bought some live continental red squirrels in Leadenhall Market and released them on his estate. The ‘native’ red squirrels in the forest were found to be from this original stock. Incidentally, Fitter maintains that the grey squirrels moved into a niche vacated by red squirrels following a catastrophic plague of squirrel pox: he suggests that red squirrels always preferred coniferous forest, and that they were forced into deciduous forest by sheer force of numbers.

As you might expect, there is also a lot about London’s bombsites. I found this photo interesting because it is just around the corner from where I now work. Who can imagine prime London real estate laying vacant these days?

Fitter even has a list of the flowering plants and ferns recorded from bombsites: I note that 88% of them had rosebay willowherb as a feature. What a sight it must have been with all those cerise flowers painting the debris! And there are also the absences: not a single mention of rose-ringed parakeets, for example, nor of collared doves, but much talk of the house sparrows in St James’s Park. I also remember the clouds of little birds that would settle on the head and arms of one particular man who used to feed them. How much things change, and how fast! And how precious are the creatures and the plants that remain.

Coltsfoot on a bombsite

A fascinating glimpse of the guides you find so useful. We take a box filled with books about trees, flowers, birds, animals and even rocks when we (used to!) journey around the country. It is great to learn about nature when you are actually confronted by something you wish to read about in the field.

Yep, I love that moment of connection when you identify a creature or a plant, or see some behaviour that you’ve only read about!

Loving your delving into your bookshelves.

There is a delicious irony that city dwellers have become the most enthusiastic custodians of our natural heritage. Urban gardeners are credited with doing as much if not more for bee diversity than our country cousins.

Your choice of yew reminds me of our 2018 trip to see the Fortingall Yew (which has claims to being the oldest living thing in the UK if not Europe.

(Line 4 of your post seems to have gone AWOL, but your intention is still clear.)

I think the big problem in the countryside is the monoculture in many areas, the cutting down of hedgerows, the pesticides and the more efficient harvesting, plus the complete impoverishment of the soil, though I do see individual gardeners and farmers going to extraordinary lengths to try to put things right. But yes, there was a recent study that said that there was more biodiversity in suburban areas now than in ‘the countryside’ per se.

I would love to see the Fortingall Yew! The Totteridge one is thought to be over a thousand years old, but I think it’s a junior compared to the Fortingall Yew.

Thanks re the typo, I will have a look and see if I can remedy it…

Just to mention that the Fortingall Yew is more like a ring of trees because the middle has died back. This process was accelerated by people setting fires and otherwise abusing the landmark.

Protecting fortifications have been built around it, rather detracting from it’s naturalistic setting. The disparate parts still share their root system. I am reminded of Merlin’s oak tree in Carmarthen which ended up as a blackened stump in the middle of a busy road. It had metal bands around it to protect it as the belief was that disaster would befall the town (or probably all of Wales) when the tree fell.

The Totteridge Yew is hollow too – I think I read somewhere that trees often lose their heartwood because it’s something of a liability, but I forget the details. It’s always interesting to see how ancient trees are both abused and protected – I’ve seen some ancient oaks that are pretty much held up by metal struts, and protected by spiked fences. Interesting how our ancient beliefs about trees are both ignored and upheld…